Newsroom

Expert Uncovers America’s Long History of Conspiracy Theories

Author and Reason magazine editor Jesse Walker virtually visits class on 20th century U.S. history.

If American politics seems overwhelmed with conspiracy theories today, it may simply be sticking with tradition.

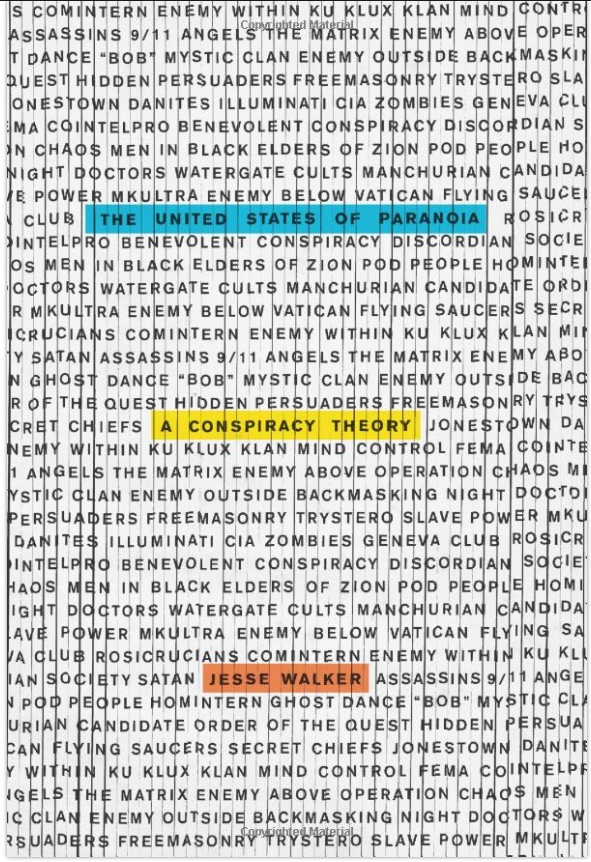

That was the takeaway from John McCarthy’s upper-level class on 20th century American history during a virtual visit by conspiracy theory expert Jesse Walker. The editor at Reason magazine and author of The United States of Paranoia: A Conspiracy Theory told McCarthy and his students that Americans worried about conspiracies long before the nation was established.

For instance, he said, historians still don’t really know for sure what happened in the alleged murder that sparked the bloody King Philip’s War in 1675, costing the lives of thousands of New England colonists and Native Americans. Even the circumstances of America’s creation and the motives of its founders have been called into question, he argued. Suspected cabals and enemies come in all political stripes, both from abroad and from within, from the top and bottom rungs of the social hierarchy alike.

“Certainly in the last few years there’s been a lot of rhetoric, especially since Donald Trump became president, there’s been a lot of anxiety about losing the concept a shared truth,” Walker told students in the online session during a Wednesday class in October. “But there’s never been a shared truth, and people have always been arguing about basic elements of reality.”

McCarthy, who recently taught and lectured in Slovakia as part of a Fulbright Scholarship, specializes in immigration and urban history as well as modern U.S. history. After interacting on Twitter with Walker, McCarthy persuaded the writer, whose wife is from Pittsburgh, to talk to his RMU history students about Americans’ long fascination with conspiracy theories.

“I tell my students I think Americans have good reasons for entertaining conspiracy theories, even if some of them are totally silly,” McCarthy says. “The CIA did a lot of things underhandedly between 1945 and the end of the Cold War. There are conspiracies that exist. One of the reasons why I think this book is useful is that Walker contextualizes this, and says this is a part of American history.”

Walker spent most of the class taking questions, many of which related to present-day conspiracy theories and related topics such as the rise of Q Anon and the climate of suspicion surrounding Covid-19 and vaccines. As for the best way to challenge others’ beliefs in conspiracies, Walker said that depends on how strongly a person wants to believe a theory is true.

“Generally speaking, either people understand what real evidence is and are open to receiving it or they’re not,” Walker said. “I don’t think there’s any kind of magic formula. I just think that in general all you can do is, to the extent that people are receptive, show them what the other ways of looking at the issue are.”