Newsroom

Poetry Remembers the Loneliness of War

Textbook by English professor Connie Ruzich shares new voices from World War I.

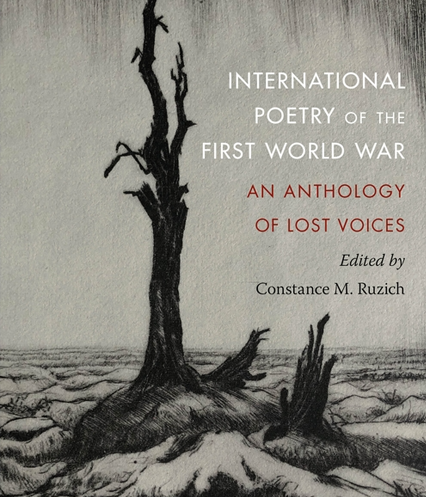

A textbook collection of poetry edited by RMU English professor and former Fulbright scholar Connie Ruzich introduces new voices into the standard World War I canon. Her new anthology, International Poetry of the First World War: An Anthology of Lost Voices, is published by Bloomsbury Press. Ruzich wrote the following essay for Veterans Day:

War is a lonely business. And as we struggle through a global pandemic that has been marked by increased social isolation, we are learning the costs of what researchers term the “loneliness epidemic”: an increased risk of high blood pressure, heart disease, cognitive decline, and mortality.

Film, fiction, and memoir testify to the value of comradeship that soldiers find in combat, but military service, particularly in war-time, also intensifies soldiers’ sense of estrangement and alienation. The geographic mobility and frequent redeployments that are required can lead to a sense of rootlessness, and numerous studies have found that loneliness and social isolation pose critical problems for veterans of all ages.

Edward Thomas’s poem “Rain” never raises its voice above a whisper as it contemplates the loneliness of war. In July of 1915, the 37-year-old Thomas decided to enlist in the British Artists Rifles, and “Rain” was written while he trained in Essex. Sent to the Western Front in early 1917, Thomas was killed on Easter Monday of that year.

Rain, midnight rain, nothing but the wild rain

On this bleak hut, and solitude, and me

Remembering again that I shall die

And neither hear the rain nor give it thanks

For washing me cleaner than I have been

Since I was born into solitude.

Blessed are the dead that the rain rains upon:

But here I pray that none whom once I loved

Is dying tonight or lying still awake

Solitary, listening to the rain,

Either in pain or thus in sympathy

Helpless among the living and the dead,

Like a cold water among broken reeds,

Myriads of broken reeds all still and stiff,

Like me who have no love which this wild rain

Has not dissolved except the love of death,

If love it be towards what is perfect and

Cannot, the tempest tells me, disappoint.

Shortly before he died, Thomas wrote his wife, “It becomes harder for me to think about things at home somehow. Although this life does not absorb me, I think, yet, I can’t think of anything else. I don’t hanker after anything. I don’t miss anything. I am not even conscious of waiting. I am just quietly in exile, a sort of half or quarter man.…”

Brian Tam writes, “Loneliness is something all service members can relate to. Homesickness is part of the job.” John Allan Wyeth, perhaps America’s finest poet of the First World War, writes of the loneliness of deployment aboard a crowded ship sailing to France and the Western Front in 1918, in “The Transport”:

A thick still heat stifles the dim saloon.

The rotten air hangs heavy on us all,

and trails a steady penetrating steam

of hot wet flannel and the evening’s mess.

Close bodies swaying, catcalls out of tune,

while the jazz band syncopates the Darktown Strutters’ Ball,

we crowd like minnows in a muddy stream.

O God, even here a sense of loneliness…

I grope my way on deck to watch the moon

gleam sharply where the shadows rise and fall

in the immense disturbance of the sea.

And like the vast possession of a dream

that black ship, and the pale sky’s emptiness,

and this great wind become a part of me.

Wyeth’s poem is eerily similar to Rupert Brooke’s “Fragment.” Writing as he sailed for Gallipoli, Brooke also found himself alone on a darkened ship, imagining his fellow soldiers as “Perishing things and strange ghosts—soon to die.” Disconnected from the men around him, the solitary soldier in Wyeth’s “Transport” resigns himself to solitude, joined only to the emptiness of the sky and the invisibility of the wind.

And then there is the loneliness of those left behind. On the day of the Armistice, when bells rang and crowds cheered the news of the end of war, millions grieved as they remembered those who would never return. May Wedderburn Cannan’s poem, “Paris, November 11, 1918,” describes two women who stand apart, walled off from the boisterous mood of joy:

‘I have a toast for you and me,’ you said,

And whispered ‘Absent,’ and we drank

Our unforgotten Dead.

But I saw Love go lonely down the years,

And when I drank, the wine was salt with tears.

Cannan would later write, “Never for us is folded War away, / Dawn or sun setting, / Now in our hearts abides always our war.”